Know Your Data

In a quick first pass at a dataset, it’s frustratingly easy to come to the wrong conclusion by not knowing what real-world-variables your data represents.

For example, I took a look at the MTA’s Turnstile Dataset to see how quickly I could find the busiest subway station in NYC. And after doing a quick sum over a variable and a time period, my answer was…

…Union Square. By a mile. The average weekly ridership (turnstile entries) over the period April-June 2015 was 68,000 people.That dwarfed the total at the next three biggest stations (Times Square, Herald Square and Grand Central), which each take in about 45,000 people each week.

And even though that seemed counterintuitive, I started to justify how that might make sense. Times Square and Grand Central are clearly commuter hubs, but Union Square is always busy, even on nights and weekends. Maybe that weekend traffic gave Union Square a boost.

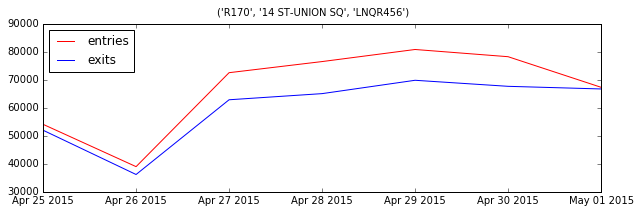

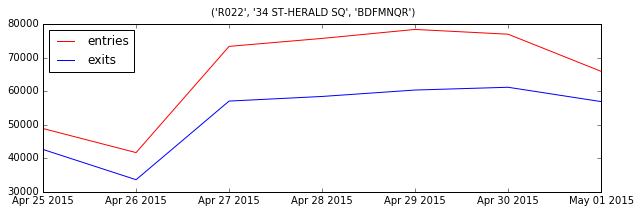

But, a plot of Union Square shows no big boost in weekend traffic compared to Herald Square. So I took another look at the data I was using.

It turned out the variable I was using for station (MTA’s ‘‘remote unit’’) is not wholly representative of a station! Some stations, like Grand Central, have multiple ‘remote units’. Another look at the top 50 showed Grand Central on there twice. And Penn Station was there three times. It turns out 95,000 people get on at Penn Station each week, across three ‘remote units.’

So, two pitfalls to avoid in early analysis. First, investigate your variables! That might involve more work than just reading the README. Like talking to someone who knows the dataset, or doing some early data sweeping to check for extreme values and double counting.

Second, double check any findings that are counterintuitive. They might be a misreading of your analysis. And if you did come across something interesting, you should want to find more proof for it anyway.